“A sap-run is the sweet good-by of winter. It is the fruit of the equal marriage of the sun and frost.”

John Burroughs, Signs and Seasons, 1886

Two winters ago a friend was passing through New York on her way from Quebec and brought me a big can of maple syrup from the airport’s gift shop. Without a stack of pancakes in sight, I punctured the top of the can and drizzled it on a bit of yogurt and was overcome by its rich amber color, sweet depth of flavor and silky consistency. It was the first time I ever had real maple syrup.

Growing up in the rural foothills of North Carolina, far removed from the northeast (farther still from the cultural influences of the maple sugaring industry), I had been perfectly content in my ignorance to dress my pancakes with caramel-colored high fructose corn syrup poured from the flip-top kerchiefs of plastic plantation-era mammies.

So began my affaire de coeur with real maple syrup. Since the yearly sap harvest is drawing to a close, now seems like the perfect time to enjoy the fruits of all that labor while celebrating the history and versatility of this uniquely North American provision.

The Sugaring Process

The sugaring process (rendering sap into syrup) is labor-intensive to say the least. It all happens during a four- to six-week window during the sunny days of late winter known as Maple Sugaring Season. It is during this time that the season’s supply of maple syrup is harvested from the red, black and sugar maple trees of the greater Hudson Valley, New England and eastern Canada.

When daytime temperatures rise above 40 degrees but still fall to below freezing at night it creates a pressure fluctuation that forces sap up from the maple trees’ roots. Because such specific conditions are necessary to create that pressure, each sugaring season is unique in length and yield. There are only twenty or so prime sapping days between mid-February through early April. When the sap does flow freely, rousing the trees from winter dormancy and preparing them for spring’s reawakening, the trees are tapped and the collected sap is then boiled down into syrup.

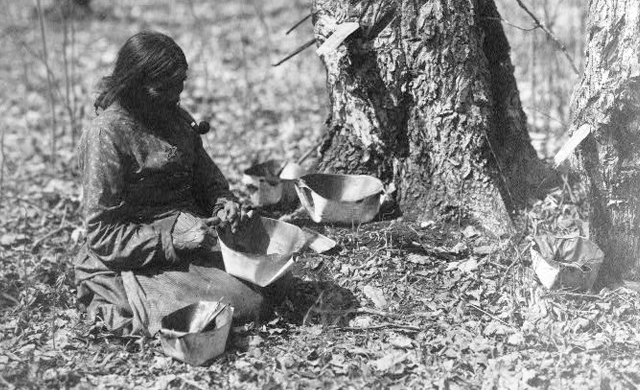

Native Americans figured out this process long before the arrival of Europeans in the new world. An Iroquois legend tells about the clever wife of Chief Woksis and the accidental discovery of maple syrup.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

The story goes that Woksis left one morning on a hunting expedition, removing a tomahawk blade from the trunk of a tree where he’d flung it the day before. As the day progressed and the temperature rose, sap poured from the gash in the tree and into a vessel that happened to be sitting nearby. Later, the wife of the chief discovered the watery substance and decided to try boiling the evening’s meal in it in lieu of trekking further for water. Later that evening when Woksis returned from the hunt, he was enamored by the aroma of the rendering syrup from far away, and so began the tradition of maple sugaring.

Whether that happy accident actually took place we’ll never know. But we do know that French explorer Jacques Cartier observed Native Americans tapping maple trees in 1540 and there are written observations of the Native Americans’ sugaring process dating back to 1557. The earliest of these observations discuss how sap was held in a hollowed-out log of basswood and heated stones were used to evaporate the water.

The mechanics of the process have evolved immensely since those days but the basic tenets of production still hold true. Well into the 20th century sugar producers would punch a v-shaped gash into a maple tree, insert a wooden or metal spout and then hang a bucket to catch the sap.

Today this method has given way to more efficient and complex systems of plastic taps and tubing that carry sap from many trees to one central holding tank by relying on gravity.

Photo Credit: Cedervale Maple

After the sap is collected, its excess water must be boiled away. A gallon of syrup requires approximately 40 gallons of sap. Many syrup producers first use reverse-osmosis devices to remove the sap water without heat. This energy-efficient method enables approximately 75 percent of the water to be removed before any heat is introduced. Once the concentrate reaches about 66 percent sugar (as opposed to sap’s 2 percent), it is ready for filtering and bottling. (It can also be further processed into maple cream and maple candy — a favorite treat at your local farmer’s market.)

A Drizzle a Day…

Maple syrup is the definitive topping for flapjacks, french toast and waffles but it has a host of other uses in dishes both sweet and savory. One of my favorites is easy and delicious. I cut a butternut squash in half, hollow out the center where the seeds are, stick in some cloves and then pour maple syrup directly into the cavity. Roast it until the flesh is tender, take out the cloves and mash up the syrup-infused squash into a hearty and delectable side dish.

You can also substitute maple syrup for white sugar in many recipes. Because it has nutritionally significant amounts of manganese, zinc, calcium and potassium, maple syrup can make your next homemade dessert a little more healthy and guilt-free. Substitute ¾-cup of syrup for 1-cup sugar and reduce the liquid content of the recipe by three tablespoons for each cup used.

Hudson Made offers real maple syrup from Sugar Hill Farm in Pine Plains, NY. In addition to its annual maple production, the farm also produces responsibly raised Berkshire pork and Black Angus beef. Consider glazing your steak with maple syrup combined with a pinch of cayenne pepper for a sweet and spicy flavor combination. I’ve been known to drizzle it on popcorn. Or put a dash in my favorite cocktail. And on a rare occasion, I have been known to just take a swig, right from the bottle. Why not?

Click here to learn more about Sugar Hill Farm’s maple syrup.

Looking for the ultimate culinary gift set? Consider “The Flap Jack.”

Sloan Rollins is a freelance writer who contributes regularly to Hudson Made’s ecommerce site. His work has been seen in Time Out New York, and he is a music and theater critic for edgeonthenet.com. sloanrollins.com