I have that kind of Scottish-Irish hair that doesn’t grow long, but rather wild, wavy and very big. I first started growing out my hair in college after 18 years of buzz cuts. My lush and loose locks were a new ‘me’ to present to a world away from home, but these curls were full of volume and challenging to coif. Then I discovered the prowess of a bandana to rein in my tempestuous mane. This timed perfectly with that moment in pop culture when Madonna made everything western cool again with embellished bell bottoms, studded leather belts with oversized buckles, cowboy hats, fox tails and of course, bandanas front and center. I was riding the crest of fashion. When I went to see Madonna’s “Drowned World Tour” that summer I wore an American flag bandana. Yes, I was that guy.

In spite of its simplicity, the bandana is that rare fashion hybrid—an item that’s as stylish and classic as it is utilitarian. Image courtesy of stylist/blogger Francis Kenneth Anunciacion, photo by Sylvia G Photography.

Like a lot of styles Madonna has adopted through the years, the pop icon did not invent the bandana, but reimagined it in a way that was both modern and relevant. Kerchiefs, the forefather of bandanas, can be traced to the French aristocracy. The plebian class couldn’t afford the fine, white silks that the upper class enjoyed. They wanted a more work-friendly accessory and the dark, printed cotton scarf emerged. The adoption of the bandana was both a necessity and an act of rebellion against the bourgeois. Other European countries soon followed suit and the bandana was on a roll. No matter where the bandana turned up, from the beginning it was a symbol of the proud, workingman—even if some of these men worked on the wrong side of the law. Pirates who plundered gold- filled Spanish galleons off the Caribbean Sea soon introduced bandanas to the New World.

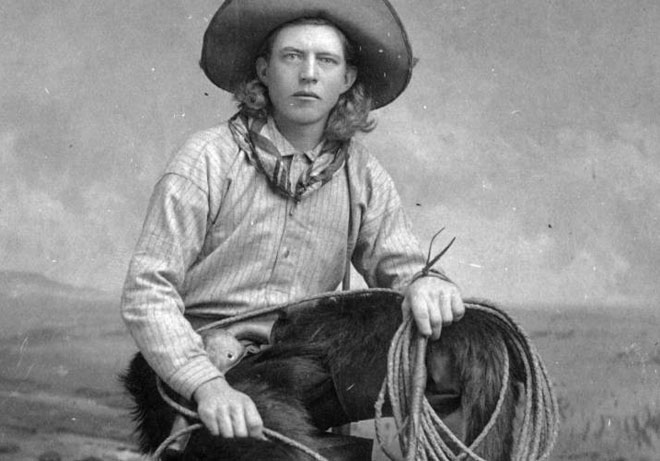

Portrait of a cowboy by Charles D. Kirkland, circa 1880. Image source: Denver Public Library Digital Collections.

It wasn’t just criminals that knew the benefits of a good bandana. Outdoor laborers, such as farmers, railroad workers and cowboys wore them around the neck to wipe the sweat off their faces and keep dust out of their collars. Miners and factory workers concealed their mouths with bandanas to lessen the dust and fumes they inhaled. These cotton scarves were far more practical than the standard white hanky. The saturated colors and patterns hid stains more effectively and made them more durable. This proved useful to soldiers who took advantage of the bandana’s versatility to keep their own sweat and opponent’s blood out of their eyes. On the battlefield, a bandana could be used as a tourniquet for the wounded.

The history of the bandana is inextricably linked with the history of workers. Here, a riveter wears a bandana on her head while posing atop the wing of a WWII bomber at the Burbank, CA Lockheed Aircraft Corp. factory. Image credit: Life Photo Archives, circa 1942.

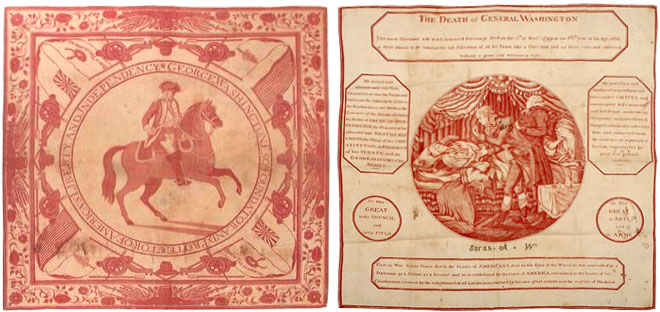

Beyond practical purpose, the bandana found a new role during the Revolutionary War: propaganda and promotion. Martha Washington used a printed bandana as a huge political “f*ck you” to the British who put a ban on textile printing in the colonies. Going one step further, Washington wouldn’t dare display any old print. She met with John Hewson, a printmaker friend of Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, to craft a cotton creation for her husband to use for political purposes. He returned with an image of canons, flags and George Washington on horseback. This very image was then used as propaganda in the war and when the British were defeated, as a commemorative souvenir. A new design was manufactured upon George Washington’s death. Because of the first lady’s keen fashion statement, the political bandana was born. Since then many historical milestones (world wars, the walk on the moon, the fall of the Berlin Wall, etc.) have had their own commemorative bandanas.

At left, the John Hewson-designed bandana commissioned by Martha Washington during the Revolutionary War, depicting the first president on horseback (image credit: New York Historical Society). At right, a commemorative bandana created upon George Washington’s death in 1799 (image credit: 1812 War & Piecing).

Bandanas also emerged as social identifiers. In the 1970s, the gay community adopted a “hanky code.” The colored bandanas indicated one’s orientation and sexual preferences without drawing unwanted attention from the rest of the world. Continuing bandanas connection to anti-authority, gang members in the 80s also appropriated bandanas as communication tools. This time the colors referenced loyalty to one gang or another: red meant Bloods; blue meant Crips.

A classic paisley bandana pattern.

From the streets of Los Angeles to Hollywood’s glitz and glamour, Madonna isn’t the only pop culture personality that has put the bandana front and center. Other recording artists have showcased the piece either by flaunting or rebelling against its deep-seated roots in the working class. Some have embraced its working class connotations, like Bruce Springsteen, who proudly claimed he was “Born in the USA.” Joan Jett personified rocker chick extreme by wearing a solid neck bandana on her album cover “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll.” Axl Rose’s L.A. bad boy swagger couldn’t have been complete unless he, too, held back his hair with his signature bandana headscarf. Jennifer Lopez, during her Puff Daddy phase, delivered her dual image of ‘Jenny from the Block’ / DIVA with a blinged out bandana neatly knotted behind her ears.

From the coal mines of France and our country’s first ‘first lady’ to today’s cultural icons, the bandana has firmly secured its place as part of America’s fashion history. It continues to be pragmatic and versatile. And to paraphrase Madonna, who inspired my own personal bandana phase, it makes the people come together.

|

|

|

| Patriot with Panache | Bandana | The Well-Worn Traveler |

Mac Smith is a New York City based fashion writer who has never met a cat, coat or cake he didn’t love. itcantallbedior.blogspot.com twitter: @itcantallbedior