“Clothes make the man”

–Mark Twain, American writer

If Mark Twain was correct, then the high school version of me—donned in a mandatory cheap polyester apron, polo shirt and shapeless pants—knew my place. And it wasn’t at the top of the fashion food chain. I was working for a major bagel store (back when bagels were a thing) and the aforementioned outfit not only shielded me from continuous cream cheese assault but also from the world. This was my first foray wearing a uniform and my last. As a young guy with a burgeoning interest in fashion, design and textiles, I made a pact then and there I would never wear a uniform again. And while I’ve kept good on that day’s promise, I’ve opened my eyes to the world of workwear and its intrinsic chic, minimalist style. I’m not alone. The whole world of fashion is smitten with the clean lines and classic functionality of workwear. Some of my favorite designers reference workwear season after season while editors, stylists and bloggers have latched on to the ease and laidback luxury of pieces that were built to move.

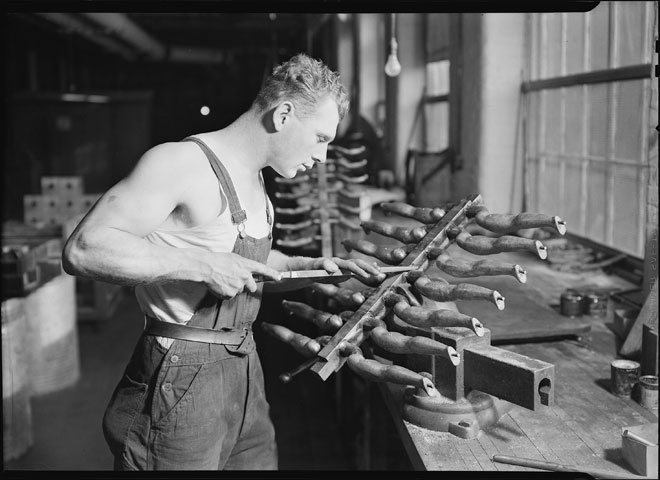

A factory worker at the Paragon Rubber Co. plant in Mount Holyoke, Massachusetts. Photograph by Lewis Hine, 1936; image courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.

Not a whole lot has been written about the evolution of workwear. I thought the Internet would be abuzz since workwear has captured the hearts of street style denizens, but I did discover an informative book, Workwear: Work, Fashion, Seduction by Olivier Saillard and Oliviero Toscani (Mode, 2009). This is a comprehensive look at workwear’s impact throughout fashion history, its present prominence and its place as the uniform of the future. In between the impassioned words are striking photos of classic jackets, gloves and even gas masks as well as the fashion editorials and runway collections that have embraced and exaggerated the innate style of these items over the years.

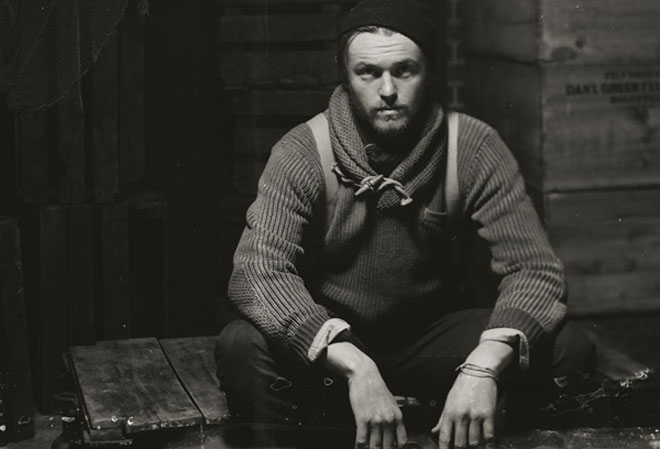

Coal miners in Birmingham, Alabama, 1937. Photograph by Arthur Rothstein; image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Workwear originated in the professions of the earth such as farmers, coal miners, butchers, etc. where the need for a strong and resilient uniform emerged. These pieces had to perform just as hard as those who wore them and were never mistaken for stuffy and showy banker suits and office shirts. Workwear designs were durable and made of unfeigned fabrics like denim, waxed canvas and flannel. These materials were both more versatile and more affordable for the working class and allowed the everyman to get the job done.

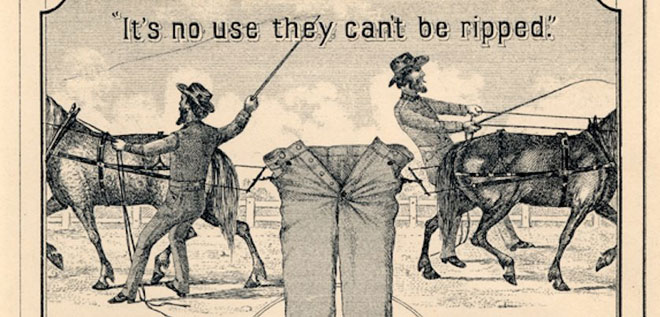

The Levi’s Two Horse Logo was first branded onto the leather patch of the 501® jeans in 1886. The purpose of the graphic was to tout the strength of Levi’s pants. Image credit: Levi’s Facebook page.

Workwear is instinctively part of the American cultural anthropology. Big names in the field come from the USA including: Carhartt, established in 1889 in Dearborn, Michigan; Levi’s, originally created in San Francisco in 1853; and Red Wing shoes, named for the town in Minnesota where it was founded in 1905. At first workwear was purely agricultural in nature. During and following the Industrial Revolution and urbanization, people left the fields for the factories and railroads and workwear evolved to offer protection, breathability and comfort to these journeymen.

Alongside Levi’s and Carhartt to name a few, Red Wing shoes is a brand whose status as a long-standing, storied American company has cemented it as an important force in contemporary workwear fashion. Image credit: Clément.

Over time, these brands have seamlessly melded into modern, mainstream fashion, where they are more popular than ever. Workwear has experienced a surprising resurgence with young artists and urban dwellers who are attracted to the minimalist designs. Mainstream consumers have re-discovered workwear as the pendulum swings back toward quality construction over disposable, fast fashion. “Made in America” is also a major selling point. New artisans have crafted a niche in workwear and styles influenced by classic uniforms. Brands such as Joshu+Vela and J.L. Lawson & Co have firm roots in workwear but with forward vision and design. The Hudson Made Worker’s Apron also offers utility, relevance and practicality in the face of any job.

The Hudson Made Worker’s Apron, with its heavy-duty canvas and buckskin leather straps, is well suited for any manner of work—be it in an artist studio, a carpentry worskhop, or a kitchen.

Yet workwear has romanced high fashion as well. The techniques and craftsmanship have leapt from the fields and factories to the runway. And like many things in high fashion, Chanel is to blame. Coco Chanel famously chose comfort over constriction bringing chambrays and wide leg pants, styles associated with working hands, to the upper echelon post-World War I. In 1939, Chanel’s main competitor, Elsa Schiaparelli, also embraced workwear with a stylized overall. Designed in heavy midnight blue wool and proudly showcasing an exposed zipper that divided the overalls along the whole of the garment, Schiaparelli called it the Tenue d’Abri (translation: shelter suit). Schiaparelli cheekily stated that this was her suggestion for women looking for a rugged yet elegant one-piece to rapidly don before taking refuge in an air strike cellar during World War II. Mid-century saw denim, sweats and undershirts become de rigeur with Hollywood embracing the looks of the working class.

In the 1980s high end designers like Ralph Lauren started romanticizing the American worker and the iconography associated like trains, industrial equipment and farms. Lauren’s love affair with workear continued with his Spring 2012 menswear collection— a modern interpretation of Americana featuring rugged coated canvas, leather, cable knits and denim pieces. Rei Kawakubo, creative director of Comme des Garcons, has also shown many collections devoted to the work aesthetic, including the nouveau interpretation of railroad and chain gang stripes for Fall 2013.

The Spring/Summer 2012 collection for RRL was heavily influenced by workwear. Image source: Aspects of Cool.

But no designer truly fell in love with the construction and legacy of workwear like Yohji Yamamoto. Workwear: Work, Fashion, Seduction describes his introduction to the genre through the photographs of August Sanders who captured farmers and workers in their everyday garb. Yamamoto instantly was enamored with the patina on the workers garments and how the history of their experiences shined through their uniforms. It’s not just their form and structure, but the way time leaves its indelible mark on the pieces. In his spring 2003 collection, Yamamoto showed a series of six overalls, each increasing with grandeur and routine. This was a love letter to the rudimentary clothing that has taken over his thoughts. According to Style.com, Yamamoto’s fall 2013 collection features a series of “stripped-down black looks that were actually far from simple—complex, technical cutting prevailed in this workwear-inflected section, as it did throughout.”

Where is workwear headed next? The possibilities are as endless as the allure. A new generation steeped in urban and skate culture has appropriated workwear as its own, identifying with its social origins and blank canvas for interpretation. And really that’s always been the appeal: workwear reimagined in a way that is both modern and also pays homage to its utilitarian roots. I just hope it doesn’t involve bagels with cream cheese.

Discover these workwear-inspired products at Hudson Made:

|

|

|

| Bourbon Worker’s Apron | Worker’s Soap | Canvas & Leather Dopp Kit |

Mac Smith is a New York City based fashion writer who has never met a cat, coat or cake he didn’t love.