Second Installment in a Two-Part Series

“Wildman” Steve Brill, who had an interest in healthful gourmet cooking, was out for a bike ride when he came across a group of ethnic Greek women dressed in black among the greenery in Cunningham Park, Queens. As he likes to tell it, “I asked them what they were doing but it was all Greek to me!” He went home with grape leaves, which he stuffed “and they were delicious.” When I met Brill, I thought in some ways he could be the spiritual son of Gibbons—he is quite the raconteur. Brimming with enthusiasm, he delivers his wisdom with a unique sense of humor. On the mullein plant (sometimes referred to as cowboy toilet paper), he has this to say on his website: “Women who were forbidden to use make-up for religious reasons rubbed the rough leaves of this rubefacient on their cheeks, to create a beautiful red flush. People who spend time in the woods are attracted to mullein’s large, velvety leaves when they run out of toilet paper, again creating a beautiful red flush on their cheeks.” He has been foraging and leading tours since 1982, has written several guidebooks and wild edible cookbooks, and has produced a master foraging app for mobile devices, “Wild Edibles Plus.”

At left, “Wildman” Steve Brill (image courtesy Steve Brill); at right, the spoils collected by a participant in one of Brill’s Central Park foraging tours (image credit: Fred Benenson).

On a recent tour with him on the Appalachian Trail in Pawling New York, I was surprised when two members of our group reported being accosted by an irate hiker who was not happy to see them digging up burdock plants. The familiar admonishment issued by many parks services, “take only pictures, leave only footprints,” needs to be revised. Many harvestable plants are actually invasive species. Picking endangers few.

The flora of the Appalachian Trail in New York. Image credit: Renee McGurk.

I would agree with Brill that nature is not a museum to be viewed from behind a velvet rope. Nothing gives you a greater sense of place and respect for nature than being able to gain sustenance from it. “I haven’t seen any danger to the environment from 31 years of foraging repeatedly in the same places with large groups… no decline in the dandelions, lamb’s quarters, burdock, sassafras, or chicken mushrooms anywhere we’ve been harvesting these renewable resources.” He recently led a record-breaking 81-person tour in New York’s Central Park. “The mowers will still be moving in to cut down the same ‘weeds’ we’d eaten. Of all the threats to the environment we’re facing, ecological harvesting of common weeds doesn’t even make the list.”

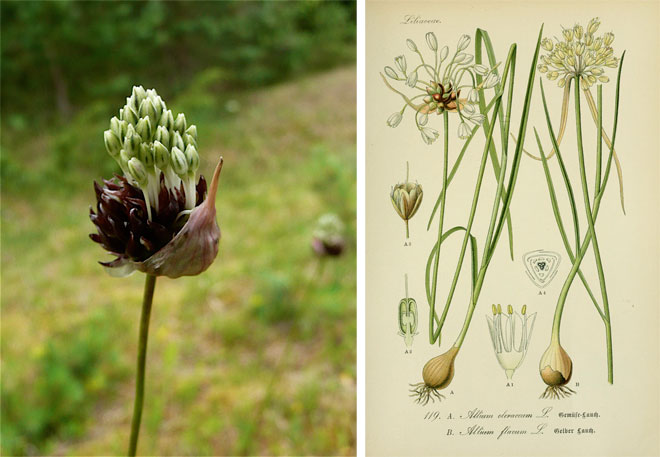

Many of the local foragers I interviewed and have met online (or in the woods) cite Wildman Steve Brill as the person who introduced them to collecting edible wild plants. Among them is Ava Chin. As a child, Chin remembers pulling up field garlic from her apartment courtyard in Queens. On her first walk with Brill in Central Park years later, she says, “Learning that so many of the ubiquitous weeds from my childhood were edible was a revelation.” Chin, who was going through personal difficulties at the time, found that foraging provided an antidote to her fears and sense of failure. “It provided insight into nature’s timing and cycles, and helped me to see the world as a place of beauty and abundance.” Now, in addition to being an English professor at the College of Staten Island CUNY, she writes about the wild edibles that grow in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene/Clinton Hill area as the Urban Forager for the local section of The New York Times. Field garlic was the first plant she profiled. You can find her recipes and learn about her foraging adventures in NYC and environs at foragergirl.com.

Field garlic. Image credits: Anna Kika and The Biodiversity Library.

Foraging is a matter of economic necessity in many parts of the world. Even in Europe people tend to know where and when to look for local wild foods like asparagus, but in the United States people are just starting to catch up. Wild foods have always been billed as healthy, but not until recently has it become known just how much more nutritious than cultivated foods they can be.

Jo Robinson’s new book, Eating on the Wild Side, recently excerpted in The New York Times, has created quite a buzz. The book isn’t about foraging for wild foods per se, but it is a guide to finding and using foods in the produce aisle that most resemble their wild counterparts. Robinson explains how we have unknowingly bred many of the nutritious qualities out of the vegetables and fruits we eat. Based on ten years of research and analysis, she compares and contrasts the nutritional profiles of wild plants and their cultivated cousins, like dandelion greens, which have seven times more phytonutrients than the “superfood” spinach. One could extrapolate that adding even small amounts of highly nutritious wild foods to your diet can have quite a substantial benefit.

This new information may make the latest wave of interest last longer than in the past. Steve Brill also credits the effect of information technology. Facebook groups like “Foraging for Everyone,” “Forager’s Unite!” and “Edible Wild Plants” provide forums where people can trade recipes and help each other identify plants. “People can communicate with each other, whether they’re preppers, vegans, freegans, environmentalists, science geeks, or parents with nature-hungry kids.” Ava Chin would also add to the mix foodies excited by recent culinary trends.

Beet and crab salad with purselane from New York City’s Print Restaurant.

Innovative Nordic cuisine has been inspiring the use of foraged foods in high-end restaurants. René Redzepi of Denmark’s Noma, voted best restaurant in the world for the past three years, may have started the culinary ball rolling by featuring items like deep fried moss, sea buckthorn leather, and wood sorrel granita on his menu. US restaurants that emphasize local ingredients are now increasingly adding wild foraged foods to their menus. Many even employ foragers or buy from full-time professional ones. Meghan Boledovich, a menu consultant and “urban forager” for Print Restaurant in New York City, procures chickweed, lamb’s quarters, and other wild foods from local farm distributors who now include them on their availability lists. Aside from their health benefits and the new spectrum of flavors they offer, they are the ultimate local food, and they’re also hyper-seasonal: “Some things can only be found for a week or two; they really give a sense of the place (terroir) and time to the diner,” says Meghan, who also notes that it can be challenging to translate to the customer what certain things are, but “luckily certain wild foods like ramps and purslane have become popular, so I think the baseline knowledge and curiosity is there.”

A White and Green Asparagus Pine dish served at Copenhagen’s famed restaurant Noma. Image credit: Sarah Ackerman.

If you’re interested in foraging, the free version of Wildman Steve Brill’s app, Wild Edibles, which covers the twenty most common backyard species, is a good place to start. You can pick up a guidebook, do research online, or join social network groups to find out more. But the best way to learn safely is to take a tour or class with a forager who has expertise in the plants of your area. Be patient, don’t try to learn everything at once, and never taste-test, as even a small bite of the wrong leaf can have you foraging at the emergency room, which isn’t nearly as fun as your local park or woodland.

Read Part I of our foraging series—Digging Deep: Foraging through History.

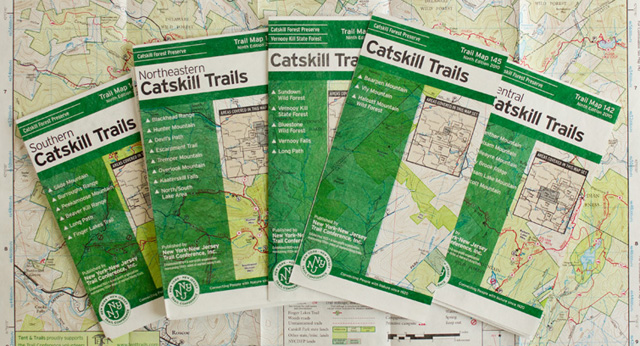

Discover the native vegetation of the Catskills with the help of these Catskill Trails Maps:

|

Lisa Kelsey is a Dutchess County, NY-based art director. Her radio shows “Stirring the Pot” on home cooking, and “Spice: The Final Frontier” on herbs and spices, can be heard on Pawling Public radio. pawlingpublicradio.org.