First Installment in a Two-Part Series

“A weed is a plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.” Ralph Waldo Emerson

I was raised in the country and I wanted my children to have the benefit of a clean, natural environment as well—that was one of the major reasons my husband and I decided to relocate to the Hudson Valley from Manhattan. I spent my childhood wandering among widely spaced oaks, amid the scent of wild oat grass drying in the sun. The golden hills of northern California did not prepare me for the expanse of lush greenery that confronted me on walks in the woods near our new house in a watershed area of the Hudson Valley. Wherever I look, vegetation of all kinds seems to coil and climb and tower over everything. The vigorous growth of weeds in my garden, their ability to grow seemingly overnight, often makes me feel I am battling some kind of interplanetary spore invasion in a science fiction movie. I have jokingly said to my husband, if only we could just eat the weeds and forget about planting vegetables!

The lush, fertile hills of the Hudson Valley. Image credit: Robert Rodriguez, Jr.

All kidding aside, there are many edible (albeit uninvited) plants growing right in my backyard. I recently spotted a plant reminiscent of miner’s lettuce, whose round bright green leaves I recalled munching while hiking with a guide in the Pacific coastal forest. My young son grabbed a handful and, crushing the leaves in his tiny hands, announced that it was garlic. He was right about the scent—it was allium petiolata, or garlic mustard. It wasn’t miner’s lettuce, but it was edible. And so began my quest to pull that wild mass of green into focus by identifying the plants that grow around us, and more importantly, which ones we can eat.

A field of garlic mustard. Image credit: Flickr user Carsten aus Bonn.

Foraging for wild foods has become the latest extension of the “eat local” movement. People are scouring their backyards, nearby pastures or even urban parks for edible weeds, berries, and roots. It’s not a new activity but one of the oldest—older than civilization itself. As humans we spent the better part of 100,000 years as hunters and gatherers. Foraging is deeply embedded in our genes and it formed the primeval basis of our relationship to what grows around us. Exploiting nature’s bounty continued after the arrival of agriculture. In our area, Native Americans foraged wild foods to supplement their cultivated corn, squash, and beans. Acorns, sunflowers, plums, grapes, wild sweet potato, black walnuts and pokeweed, among many others, were gathered from the wild. Early settlers in New England foraged for berries similar to those they recognized from their homeland, but most of them probably weren’t putting cattails and acorns to good use. Sadly, with the pushing out of Native Americans, the heritage of wild food foraging was largely lost.

Various plants traditionally foraged by Native Americans in New England. Clockwise from top-left: the purple fruit of the pokeweed plant (image credit: Dennis Blythe); the flower of the wild sweet potato (image credit: Cody Hough); wild grapes (image credit: Tonreg); acorns (image credit: Focx Photography).

Wild Fruits: Thoreau’s Last Rediscovered Manuscript, a collection of essays based on Henry David Thoreau’s observations of the fruit and nut trees, berries, and other plants growing wild near his home in Concord, Massachusetts, was published posthumously in 2001. In these pre-Civil War era writings, Thoreau was already lamenting the fact that our native huckleberries and wild apples were being neglected in favor of exotic imported fruits like bananas and pineapples. He pondered the spiritual nature of gathering local wild foods. “Do not think, then, that the fruits of New England are mean and insignificant while those of some foreign land are noble and memorable. Our own, whatever they may be, are far more important to us than any others can be,” Thoreau wrote. “They educate us and fit us to live here. Better for us is the wild strawberry than the pine-apple, the wild apple than the orange, the chestnut and pignut than the cocoa-nut and almond, and not on account of their flavor merely, but the part they play in our education.”

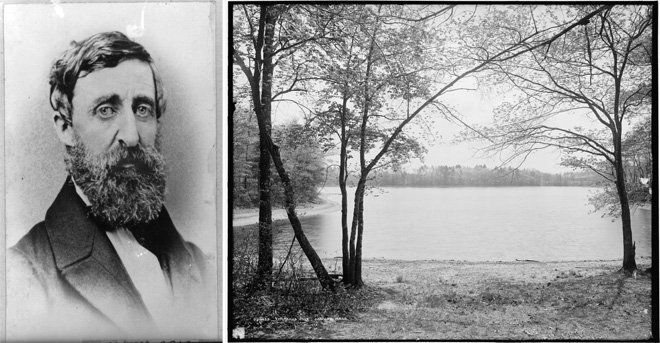

From left to right: Henry David Thoreau and Thoreau’s Cove at Walden, Concord, MA. Image credit: Library of Congress.

Thoreau would have been happy when the back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s renewed interest in wild foods. This was greatly due to Euell Gibbons, an endearing storyteller who captured the imagination of a generation. His first book on foraging, Stalking the Wild Asparagus, became an instant best seller when it was published in 1962. But Gibbons was no longhaired idealist. He was born in Texas in 1911, less than 50 years after Thoreau died. He spent most of his childhood in the parched hills of New Mexico and learned about plants from his mother. At times during the Depression when his father couldn’t find work, Gibbons provided for his family by foraging in the hills for mushrooms, piñon nuts, and yellow prickly pear. He had only a sixth-grade education but continued to teach himself by reading nature guides in libraries, asking locals how they used wild foods and seeking out the knowledge of experts.

According to veteran forager and author John Kallas, that garlic mustard my son picked is one of the most nutritious greens ever analyzed. It’s higher in fiber, beta carotene, vitamins C and E, and zinc than practically any other leafy green. There are lots of ways to use it, but I like to give it a whir in the food processor and make a nice pesto—it makes a peppery sandwich spread or you can toss it with pasta and fresh tomatoes.

Garlic Mustard and Walnut Pesto

Although garlic mustard has a nice peppery bite, I like to boost the garlic flavor by adding some garlic cloves, leaves, or scapes.

3 cups garlic mustard leaves, stems and seed pods (if any) removed, washed and drained well

3 cloves of garlic (or you can use chopped tender garlic scapes or leaves), chopped

1 cup walnuts

¾ cup olive oil or more for the consistency you prefer

½ cup grated Parmesan or Grana Padano cheese

Salt to taste

In a food processor, pulse garlic mustard leaves, walnuts, and cheese to make a paste. With the motor running, drizzle in the olive oil until the pesto reaches the desired consistency Add salt to taste and blend again.

Read Part II of our foraging series—A Walk on the Wild Side.

Discover the native vegetation of the Catskills with the help of these Catskill Trails Maps:

|

Lisa Kelsey is a Dutchess County, NY-based art director. Her radio shows “Stirring the Pot” on home cooking, and “Spice: The Final Frontier” on herbs and spices, can be heard on Pawling Public radio. pawlingpublicradio.org.