I love Coney Island. Living in New York City, I’ve always escaped to the ocean, the only place in the city that feels truly wild and untamed. But Coney Island holds a special place in my heart: still rugged beneath its gentrifying shell, it’s best in the off-season, when it’s just me and the old folks from Brighton Beach strolling the wood boardwalk.

Coney Island in April. Image credit: Flickr user Kai Brinker.

And early spring is off-season. When I arrived on a cloudy afternoon in April, even Nathan’s Hot Dogs was closed for remodeling, making the boardwalk appear especially desolate. But I wasn’t here for corn dogs. On this particular day, I was visiting for one special souvenir: a bottle of seawater.

Filling an empty seltzer bottle with seawater is more difficult than one expects in the icy Atlantic. As I waded out, a wave caught me off guard, filling my galoshes with frigid water. I was inspired to wade through the surf after coming across Hudson Made’s Bay of Fundy Sea Salt, and I suddenly wondered where salt came from in the first place.

We take salt for granted: a blue box of kosher salt costs next-to-nothing at the grocery store. But before the arrival of Europeans, the native Algonquin tribes did not manufacture salt. The salt in their diets came from the abundant seafood of the local oceans and marshes that was a staple of their diets.

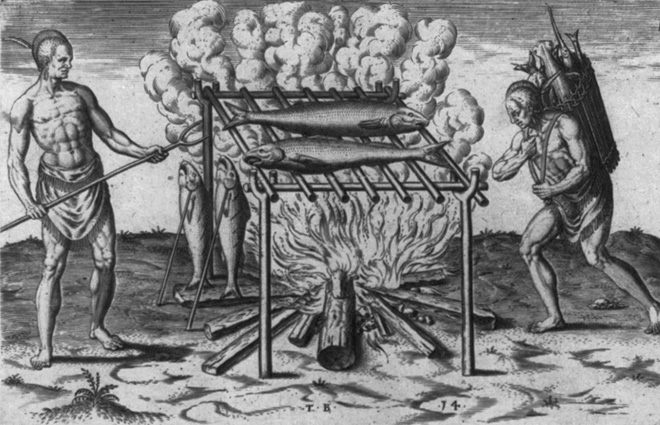

Prior to colonization, the primary source of salt for Native Americans was from the fish in their diets. In this engraving by Theodor de Bry, circa 1590, Native American men cook fish on a wooden frame. Image credit: Library of Congress.

Once Europeans arrived, salted fish (particularly cod) was one of the major exports of the colonists back to England. In order to supply the salting process, salt was imported via the British from the Caribbean. Although salt works (places where salt was crystallized from boiled seawater) were established in New England in the 1600s, they didn’t produce nearly enough salt for the colonist’s demands. When the Revolutionary War started, it really put the squeeze on—the British used blockades to make certain no salt entered American ports. The pressure inspired local businessmen to build wooden salt evaporators—large shallow trays that exposed saltwater to sunlight—around Cape Cod beginning in the 1770s. The results were meager at first, but by the 1830s they were producing over 350,000 bushels of salt and supplying most of America.

Men at the Onondaga, NY salt works raking salt from solar evaporation vats. They are working on rolling roofs of a design copied from the Cape Cod salt works. Photograph circa 1890. Image credit: Onondaga County Salt Museum, Liverpool, NY.

But evaporating salt from seawater consumed a lot of time and resources: it took 350 gallons of Cape Cod seawater to produce about 80 pounds of salt. When the Erie Canal opened in 1825, it put Cape Cod out of business. This feat of engineering created a waterway that connected New York harbor to Lake Erie, opening up the Midwest to trade. It allowed salt to be imported from Syracuse, where it was evaporated from super saline springs flowing up from huge, underground salt deposits. By the middle of the 19th century, salt was transported from enormous salt mines in Ohio and Michigan.

New York is still one of the largest salt producers in the world, producing from mines upstate, as well as by evaporation from saline springs, like Morton’s facility in Silver Springs.

After spending so much time contemplating where salt comes from, I was curious to try to produce my own salt. So I took off for my favorite—if slightly polluted—beach. When I returned to my apartment with my precious Coney Island cargo, I strained the seawater through a coffee filter to remove large impurities like sand. Then, I poured the water into a glass baking dish placed over my stove top burner, and boiled the liquid until about 90 percent had evaporated, which took approximately 45 minutes. What was left went into a 250º oven for about an hour.

And then—I kid you not—I had salt. Big, beautiful crystals along the bottom and sides of the pan. Although I knew it was science, it seemed like magic. A half-liter of liquid yielded approximately two tablespoons of salt. Will I be using it to top my salted caramel sundae or to encrust my grass-fed steak? Absolutely not—do you have any idea what they dump in the waters around New York City? But I did take a tiny taste. The verdict? Bitter and slightly metallic. I’d stick with salt from the icy, clean Bay of Fundy.

The Bay of Fundy. Image credit: Flickr user Michael Sprague.

In addition to being a great seasoning, the Bay of Fundy Sea Salt can be combined with honey and olive oil to make an effective body scrub. Read about how to make The Hudson Honey Salt Scrub in this past issue of our newsletter and shop for the components below:

|

|

|

| Bay of Fundy Sea Salt | Lucky Star Honey | Marmalade Spoon |

Sarah Lohman is a historic gastronomist. You can follow her adventures at fourpoundsflour.com.